MURPHY’S BOOKSTORE

Saturday morning, Harry Murphy awoke from a deep, untroubled sleep in his suburban Cleveland, Ohio home. He reached for the alarm clock beside the bed and shut it off before it could disturb his wife of over fifty years, who lay snoring softly beside him. She was a bear if awakened at what she liked to call the god-forsaken hour he normally rose. No sense in poking the bear.

It was a quarter to five—fifteen minutes earlier than he allowed himself these days. He hadn’t needed the alarm in years.

He padded into the kitchen and set about making coffee. While it brewed, he stood at the window and looked out onto the street. Thick, white snow fell steadily, muffling everything it touched. The driveway and road were already packed, save for a single set of tire tracks left by some other poor soul who didn’t believe in sleeping late.

“Great,” he muttered. This would keep the customers home.

By six-thirty he had parked behind the store, a full hour and a half before opening. Harry owned a small bookstore wedged between two much larger retailers on the square. The surrounding buildings had been gentrified over the years, their glass fronts and brushed steel signs gleaming where brick and wood once ruled. His shop had resisted the transformation. It stuck out like a sore thumb.

That, Harry liked to think, was part of the charm.

The building dated back to 1900, from a time when people clamored for books rather than convenience. His great-grandfather had built it, and it had passed from generation to generation before his mother left it to him. Harry had no intention of breaking the chain, though it looked increasingly unlikely that any of his children would take it on. They cited the lack of money it generated, which Harry couldn’t entirely fault them for. His mother’s modest inheritance had gone largely toward keeping the place alive.

He filled the kettle and set it on the burner, then retreated to his office to shuffle papers and straighten the previous day’s receipts. There were no computers, no monitors—just ledgers, a pen, and a scarred oak desk. He didn’t particularly care for tea, but the smell of it drifting through the store lent a certain atmosphere. Customers noticed those things.

When the kettle whistled, he went out front to prepare it. Upon returning to his office, he noticed something that gave him pause: a worn brown photo album resting on the corner of his desk.

He stood there a moment, staring at it.

Harry couldn’t recall putting it there. In fact, he couldn’t recall owning a photo album at all. He hadn’t looked through family photographs in years. Still, memory was a fickle thing at his age, and he dismissed the thought as easily as it had come.

Even so, it struck him as odd.

The telephone rang, snapping him from his reverie. It was James Amplethorpe, one of his most loyal customers, undoubtedly calling to inquire about a book.

“Harry,” James said cheerfully, his British accent unmistakable. “Top of the mornin’ to you, governor.”

Harry smiled despite himself. James had ordered a first edition Dickens novel—The Cricket on the Hearth, published in 1846—paying nearly five hundred dollars up front, commission included. Harry wasn’t complaining. James ordered through him instead of online, which Harry appreciated. Still, he’d quietly had his wife check Amazon out of habit.

“Morning, James,” Harry said. “Let me guess—you’re calling about your book.”

“Indeed I am.”

“Sorry, my friend. It hasn’t arrived. And judging by the snow, I doubt it will today.”

“Could you check with the carrier?”

“James, you of all people should know I don’t have a computer,” Harry replied. “Too old for that nonsense. I did speak with the driver earlier this week, though. He was just as much in the dark as I am.”

James sighed theatrically. “Most unfortunate.”

“I’ll call you when it comes in.”

They exchanged pleasantries and hung up. Harry shoveled the sidewalk, sold a copy of Dracula at twice its worth to a delighted customer, and settled back into the slow rhythm of the morning.

It was only then that he returned to the album.

The first page stopped him cold.

Inside were black-and-white photographs—cabinet cards, albumen prints, cartes de visite—the sort he recognized immediately from his younger days dabbling in photography. Carefully, he removed the first photograph: a woman in an old-fashioned dress, pale and formal.

He turned it over.

Elizabeth Parker.

The name gave him pause. Parker had been his great-grandmother’s maiden name. The photograph was signed in a neat hand, unmistakably hers. He had never seen it before, but there was no reason to doubt its authenticity.

“A handsome woman,” Harry murmured, returning it to its place. “Good choice, Granddad.”

The next photograph bore the name Harold Murphy, dated October 1895. Harry felt a tightening in his chest. He had never seen these images before. He was certain of it.

For nearly an hour, he turned pages. Faces stared back at him—Parkers and Murphys alike—people he had never known, yet somehow recognized. There was a photograph of the bookstore under construction, and another upon its completion. Over the door, freshly painted, were the words:

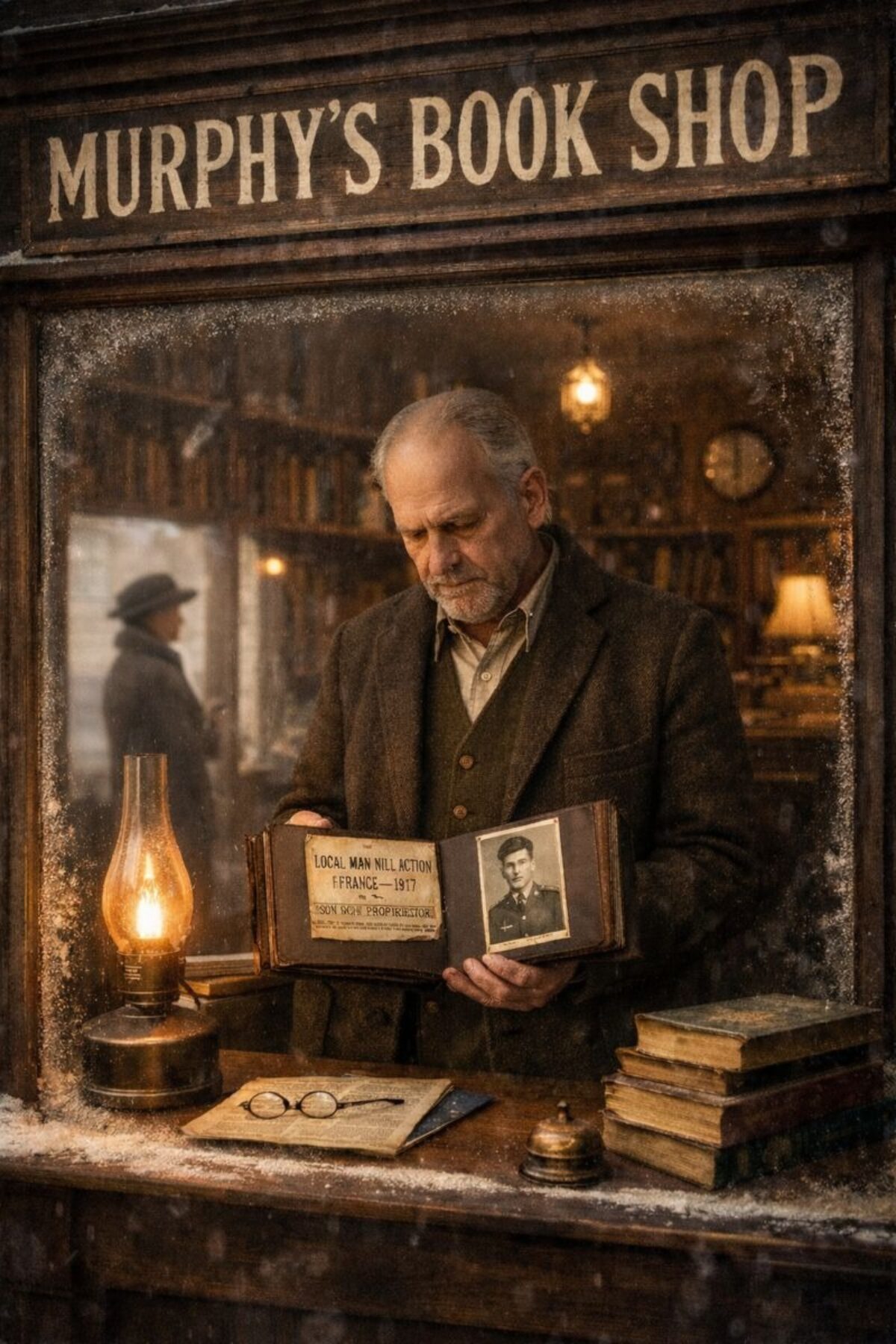

MURPHY’S BOOK SHOP

His knees ached from sitting so long. He rose and wandered the store, dusting shelves. The bell above the door chimed.

A woman entered.

Her clothing struck him immediately. A heavy wool coat, a long dress beneath it, and a bonnet. A brooch fastened her collar.

“Sir,” she said politely, “might you have Kate Chopin’s new book—The Awakening?”

Harry blinked. “If I recall, that’s a novel dealing with feminist ideas, is it not?”

She flushed slightly and glanced around the store, as though worried she might be overheard.

He located the book easily. It was bound in green cloth. The price tag read sixty-five cents.

Harry tore it off and brought the book to her.

“Fifteen dollars,” he said.

She stared at him.

“My good man,” she said slowly, “that is an outrageous sum. I buy a book here nearly every week and have never paid more than seventy cents.”

Harry shrugged. “That’s my price.”

“My husband would be quite cross with me,” she said, and with that she turned and left.

Harry replaced the book on the shelf.

That was when he noticed something else.

There were no contemporary authors. Every book dated from the nineteenth century. He pulled one at random—Essays on Literature and Philosophy, Edward Caird—priced at eighty cents. Another followed. And another.

All between fifty cents and a dollar.

“How in the world…” Harry murmured.

He returned to his office, heart pounding, and opened the album again—this time to the very back.

There was a photograph of a young man who looked remarkably like him. Beneath it was written the same name: Harry Murphy. Clipped beside the photograph was a yellowed newspaper cutting from The Cleveland Plain Dealer.

He unfolded it carefully.

LOCAL MAN KILLED IN ACTION, FRANCE — 1917

SON OF PROPRIETOR

Harry set the album down and studied the photograph again. Another image had been tucked beside the clipping—a serviceman in uniform, standing stiffly before the camera. As he leaned closer, his breath caught.

A small mole sat just above the man’s left eyebrow.

Harry raised his hand and touched his own forehead, tracing the familiar mark he had carried his entire life.

He did not panic.

He simply understood.

He glanced out through the office window. The store looked darker now. Smaller. The modern display tables were gone, replaced by worn chairs and a low table stacked with volumes by Poe, Dickens, Wilde, and Doyle. The books looked new.

They were new.

Harry rose and walked toward the front of the shop, though the space no longer felt familiar. The shelves were where they had always been—and yet they were not the shelves he had known for the past twenty years.

Outside, the snow was gone.

A woman passed by the window, dressed in a long skirt and hat, her steps unhurried. She smiled at him as she went.

Harry locked the door and walked to the corner newsstand. He purchased a paper and unfolded it carefully, his hands steady now.

He found the date in the masthead.

October, 1917.

Harry folded the paper and returned to the store.

The bell over the door rang as he stepped inside.